Content warning: violence against a 3D scan of a person

Res Extensa from Stara Diamond on Vimeo.

Spring 2020, 3D scan created with Artec Leo scanner, 3D model of Meyerson Gallery created in Maya and Unreal Engine, 2:26 minute video

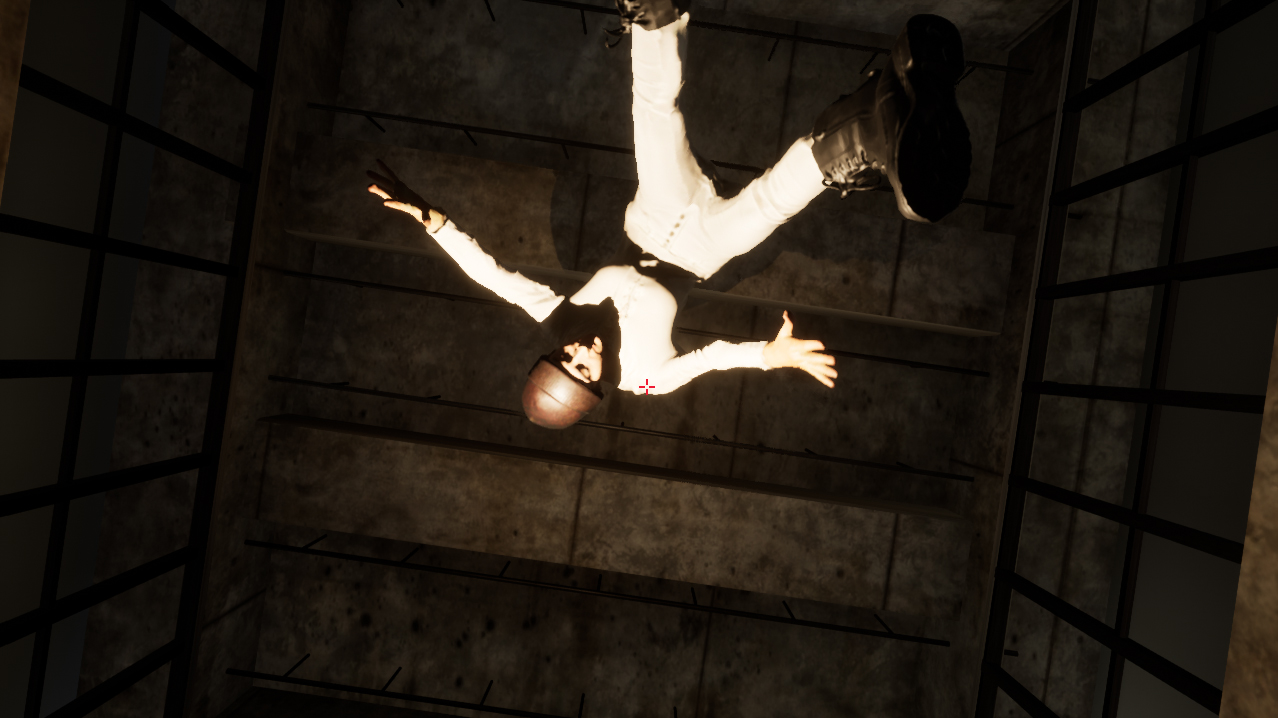

In Res Extensa, I operate a 3D version of myself, causing it to move through space. Is this not what all of us do every day? In fact, it is quite different. This body was produced by 3D scanning, and thereby separated from my consciousness and placed into the virtual world of a game which I produced using Unreal Engine and Autodesk Maya. As soon as the viewer sees the process of operating the virtual body, it becomes apparent that there is a great difference between this interaction and everyday human action. The body’s motions are clumsy, overcome with apathy, and marred by the struggle to control it without direct access to its sensory perceptions. Res Extensa is a demonstration not of everyday motion, but of detachment from one’s own body through dissociation. It is my hope that this will illuminate how crucial the unity between mind and body truly is, and the folly of the res extensa as a philosophical concept.

The nature of the connection (and disjunction) between mind and body has never been fully resolved. Some have speculated that the mind is an operator manipulating an external machine which may or may not really exist, which may be a part of a simulation or dream. This corporeal form which protrudes into the world is exhibited, according to Descartes, in the mode of res extensa, as opposed to the mind’s res cogitans. It is an entity of a completely separate substance from the mind. This is objectionable, because two objects of completely different natures could not interact in any meaningful way. But this disconnection does occur, in dissociation, and does in fact destroy meaningful interaction. A dissociating person does not feel that the mind is unified with the body. The mind feels that all sensations belong to “the body” and not to itself, that they are not certain to be real and might be part of a simulation or a dream. This defends the dissociating person against traumatic sensations, but at a terrible cost - namely, all positive sensations and all motivation.

When one dissociates, the body, as something outside of the mind, becomes a burden and a source of frustration. Its motions and responses become an object of curiosity, and rather than corresponding directly to the mind’s intentions, they fall prey to the inertia that comes of detachment. What motivation can there be to act in any way when all sensations are simply happening to a foreign object; not to the mind, but to the body? What is there to do in the empty virtual world, where I cannot feel anything the body feels? There is no fear of pain, and there is no excitement for pleasure. So the body does not cooperate - its every motion must be forced upon it by the external, tyrannous mind. And the mind exerts its tyranny aimlessly, throwing the figure this way and that but not knowing what to do with it, because it receives no feedback in the form of pain or pleasure. The sight of my limp form demonstrates the dysfunction, horror, and inefficiency of viewing ourselves in this way. The notion of the res extensa separates us not only from ourselves, but also from the world, which suddenly appears to be merely virtual, to exist in a space apart from the mind made of substances with which we can have no direct interaction.